Click here to start customizing

“Our topic now will be metals, and the actual resources employed to pay for commodities - resources diligently sought for in the bowels of the earth in a variety of ways. .... We trace out all the fibers of the earth, and live above the hollows we have made in her, marveling that occasionally she gapes open or begins to tremble - as if forsooth it were not possible that this may be an expression of the indignation of our holy parent. We penetrate her inner parts and seek for riches in the abode of the spirits of the departed, as though the part where we tread upon her were not sufficiently bounteous and fertile.”

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 77 AD

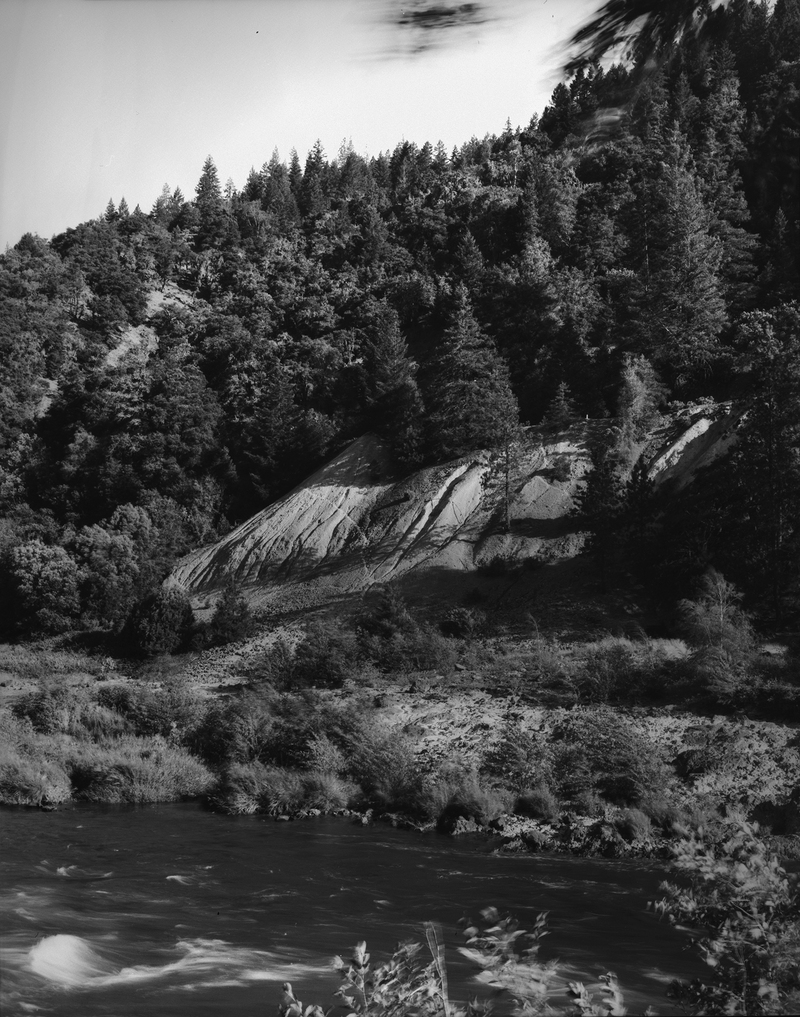

When Pliny the Elder wrote these words in Rome in the first century AD, the scale of mining today would have been unfathomable, and yet, there are mines in Great Britain from the Roman empire that are still producing pollution in the form of acid mine drainage, two millennia later. This series of film photographs and ceramic sculptures explores the toxic legacy of extractive industry through abandoned mining sites in Northern California, Southern Oregon, and Western Nevada. One of the driving forces for my regional focus in this project is the scarcity of water in the West. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, 40% of the watersheds in the Western United States are contaminated by hard rock mining.

There are an estimated 550,000 abandoned mines across the country, and over 100,000 that pose a serious environmental risk, with an estimated taxpayer cost for cleanup of $32 to $72 billion. Mining often occurs on federal land, and unlike other extractive industries (such as coal and oil), mining is governed by an antiquated 1872 law that does not require developers (often multinational corporations) to pay royalties for extracting minerals on public lands. Many abandoned mines will require extensive treatment of water for hundreds or thousands of years - essentially, in perpetuity. Mining also constitutes the world's largest waste stream. For example, it takes 5-10 tons of ore, and >10 tons of non-ore rock moved to make one gold ring.

In my artistic practice, I seek to remember that all materials in our human environment were either grown or extracted from the earth: there is no separation. In our technology-heavy era, it is mining that will meet our society's demands. As with many industries, the implementation of increased environmental regulations in the United States, instead of causing minerals to be extracted in a less hazardous way, often just leads to the colonialist practice of exporting the problem to other nations, damning their people to generations of toxicity for a short term profit. A mine has a lifespan - once depleted, they close and die - but mines are likely to be the distinguishing mark of humanity in geologic time.

With those vast scales of time in mind, my sculptures in this series evoke rock formations and ancient artifacts. They are glazed using acid mine drainage and soil samples from the mine sites. Acid mine drainage is heavy with metal oxides, which are common materials in ceramics. Through the alchemistic "purification through fire" of the ceramics process, the sculptures transmute the toxicity of these sites, returning the pollutants to an inert state - in essence, returning them to rock.

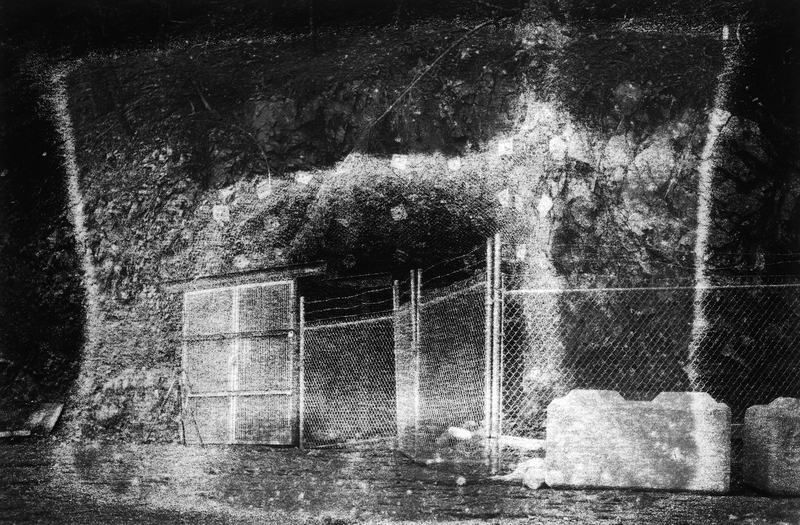

My photographs of the sites support the sculpture in providing a sense of place. They are printed with an alternative process that allows me to use long-expired paper from the 1960’s-1980s. Given the dramatic scale of many mining sites, contemporary photographers often choose an aerial view to photograph mining. Sometimes that removed perspective removes the viewer from the place, making it seem distant from the activities of our day to day lives, or translating these spaces as an abstraction. Vast aerial photographs can also make the problem seem insurmountable and invoke a sense of doom. In the words of Byron Williston, “Anthropocene environmental crises are, by definition, planetary-scale. It is tempting for individual agents to feel as though they are not able to do anything about such crises, which often leads to apathetic withdrawal from the challenges they pose or outright denial of them. … in the face of forces we can neither comprehend nor control we have become passive spectators to the upheavals we ourselves have set in motion.”

I chose a more intimate perspective to bear witness to these places, spending many hours exploring the sites and documenting from the viewpoint of being there within them. I hope that the more human scale can impact, empower, and spark curiosity, instead of distancing or overwhelming the viewer into apathy. I hope to spark conversations about mining’s environmental impact, the role of mining in society, and our issues of consumption, profit, and waste.